Three Reasons Education And Social Scientists Prefer Proprietary Software And Data Formats

When I first jumped into the world of education and social science research, I was surprised by the extent to which proprietary software and data formats were used to manage and exchange research data. As someone passionate about the use of open software and open data in scientific research, this was troubling to me.

Everywhere I looked I saw data being shipped around in SPSS, SAS, and Stata formats. What gives? Proprietary software makes analyses less repeatable, the opposite of what you want for Open Science. Proprietary data formats make data less accessible, less interoperable, and harder to reuse… the complete opposite of FAIR data principles. (Although to be fair, Stata’s dta format is an exception on this front, because at least they openly document their format’s internals).

At first, I thought the landscape was like this because of the nice graphical interfaces provided by proprietary statistical software (as opposed to coding in R or Python), as well as the network effects of vendor lock-in. And don’t get me wrong, these are big reasons! But after over a half decade of building education and social science data management and analysis pipelines using exclusively open software, I have come to appreciate other details that aren’t so obvious at first glance.

Proprietary software and data formats come with a few standard, basic features that make them particularly nice for working with education and social science data. And for whatever reason, these features don’t receive similar attention in open alternatives.

Sure, there are workarounds and ways to emulate some of these features, but I think we can do better. If we want to promote the use of open software and data formats in the education and social sciences, I think we need to provide solutions that meet these needs in more competitive ways.

The three features I want to highlight in this post pertain to the standard metadata found in proprietary formats, and how this information is used by the statistical software when loading, displaying, and analyzing research data. SPSS, SAS, and Stata data formats are convenient containers that store data alongside metadata. The metadata stored by these formats allows me to save and load data with the data types of the columns preserved, as I would with Apache Parquet, a open format used by many data scientists in open software pipelines.

Unlike Parqet, however, these proprietary formats additionally have standards for three types of metadata that the proprietary (and open) software reading these formats use in extremely helpful ways: variable labels, rich categorical types (aka value labels) and missing value reasons. As I will argue below, I believe the absence of these features are currently pain points in the adoption and usage of open software and data formats by education and social science research communities.

The Three Types of Metadata

To define these types of metadata and show how they are used by researchers in their statistical software, I’ll be using some SPSS data from Crystal Lewis’ example data cleaning workflow project here. (If you haven’t already read her blog post series detailing her data management workflow process, I highly recommend it!)

Unfortunately, I do not own a copy of SPSS, so I cannot provide you with a window into how this format looks in its “natural habitat”. However, by way of the venerable haven package, I can load the file in R and emulate most of the nice features this format allows in SPSS (with some quirks here and there, as you’ll see).

Variable Labels

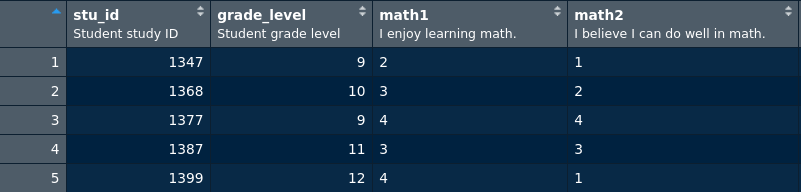

When I load a SPSS *.sav file into R using haven::read_spss()and preview it with utils::view(), I’m greeted by a table that looks like this:

df <- read_spss("w1_mathproj_stu_svy_clean.sav")

view(df)

See those subheadings under the variable names? Those are variable labels. Variable labels are short textual descriptions I can attach to individual columns.

I also get this information when I select / print a column of the table:

df$math1

#> <labelled<double>[5]>: I enjoy learning math.

#> [1] 2 3 4 3 4

#>

#> <...snip…>

Again, as you can see there at the top, there’s a description that gives me the survey text used to collect this variable: “I enjoy learning math”. Why is this nice? Well, datasets can have 1000s of variables with cryptic names. With variable labels, I can be a lot more confident I’m using the variable I’m intending to by reading its long-form description!

It also means I can use functions like labelled::look_for() to search for variables in my dataset by scanning their descriptions… allowing me to find the variables I need without having to look them up in external documentation.

Relatedly, I can use this information in scripts when I create summaries or other reports of my data. codebookr, for example, uses this information to automatically generate codebooks from my data, complete with summary statistics!

By contrast, when I load a Parquet file in R, I get column names and types, but that’s it. (And, of course, with a CSV, I only get column names… column types need to be guessed or entered manually). Yes, Parquet does have the ability to store generic metadata, so when I save a data frame in R as a Parquet file, it preserves the label attribute (which holds the variable label) as a metadata entry. But this, of course, is not an interoperable standard other applications can count on.

Rich Categorical Types (aka Value Labels)

Categorical data types are the bread and butter of education and social science research. A particularly common form of categorical data type that frequently appears in social science data are likert scales. Unlike a “pure” ordinal variable defined only by discrete, ordered options, likert scales also have numeric values attached to their levels.

In SPSS files and Stata files, they are implemented by way of numeric types with a mapping of textual labels, called “value labels”. (Open implementations of SAS formats don’t support value labels as far as I’m aware):

df$math1

#> <labelled<double>[5]>: I enjoy learning math.

#> [1] 2 3 4 3 4

#>

#> Labels:

#> value label

#> 1 strongly disagree

#> 2 disagree

#> 3 agree

#> 4 strongly agree

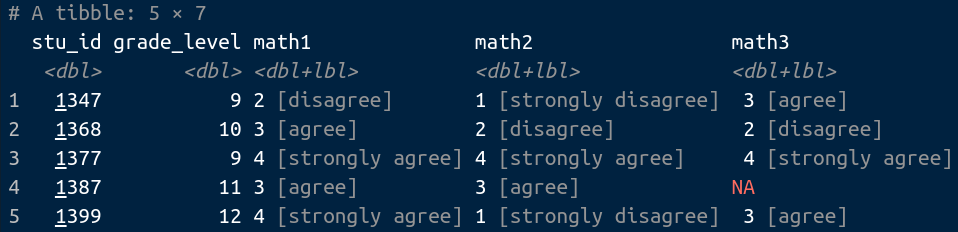

When I print out data frames with these rich categorical types, I get to simultaneously see their numeric values as well as the textual level anchors they represent:

If I want to convert these numeric responses to regular R factors, it’s a simple call to as_factor():

df |> mutate(across(where(is.labelled), as_factor))

#> # A tibble: 5 × 7

#> stu_id grade_level math1 math2 math3 math4 int

#> <dbl> <dbl> <fct> <fct> <fct> <fct> <fct>

#> 1 1347 9 disagree strongly disagree agree agree treatment

#> 2 1368 10 agree disagree disagree disagree treatment

#> 3 1377 9 strongly agree strongly agree strongly agree strongly agree control

#> 4 1387 11 agree agree NA NA treatment

#> 5 1399 12 strongly agree strongly disagree agree strongly disagree control

Why do I want both representations? Well, when I aggregate the likert items to create a composite score, I want to use their numeric values:

df |>

rowwise() |>

transmute(stu_id, mathMean = mean(c_across(starts_with("math")), na.rm=T))

#> # A tibble: 5 × 2

#> # Rowwise:

#> stu_id mathMean

#> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 1347 2.25

#> 2 1368 2.25

#> 3 1377 4

#> 4 1387 3

#> 5 1399 2.25

But I can filter by the textual value labels too, if I want! (Or use the factor labels in an ordinal statistical analysis, plots, or wherever else it’s nice to see labels rather than numeric values)

df |> filter(as_factor(math1) == "strongly agree")

#> # A tibble: 2 × 7

#> stu_id grade_level math1 math2 math3 math4 int

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl+lbl> <dbl+lbl> <dbl+lbl> <dbl+lbl> <dbl+lbl>

#> 1 1377 9 4 [strongly agree] 4 [strongly agree] 4 [strongly agree] 4 [strongly agree] 0 [control]

#> 2 1399 12 4 [strongly agree] 1 [strongly disagree] 3 [agree] 1 [strongly disagree] 0 [control]

Parquet has the capability of storing categorical data types, but does not have a standard way to attach numeric values to the levels. In other words, when I write to Parquet, I have to choose between a numeric type (thereby losing the categorical variable data type status and textual anchor info), or a categorical type (thereby losing the numeric mappings). Sure, I can keep dictionaries around that map the likert levels to numeric values, and store them in Parquet’s generic metadata, but again, it’s a custom solution and not an interoperable standard. By contrast, when I load an SPSS file, I can convert between numeric and textual / factor representations with ease.

Missing Value Reasons

A final feature shared by SPSS, SAS, and Stata data formats not explicitly supported by open alternatives is missing value reasons. When survey data are missing, there are often “reasons” attached. Maybe the person was absent the day the survey was given, maybe they skipped an item, maybe they selected the option “I don’t understand the question” when responding to the item. Researchers want the ability to differentiate between these kinds of missingness when they’re viewing, exploring, and analyzing their data.

SPSS, SAS, and Stata formats store missing reasons as codes interlaced alongside regular values, along with a map from codes to textual labels. SPSS typically uses negative numbers to represent missingness, whereas SAS and Stata will use alphabetic codes (e.g. “.a”, “.b”) to represent different types of missingness.

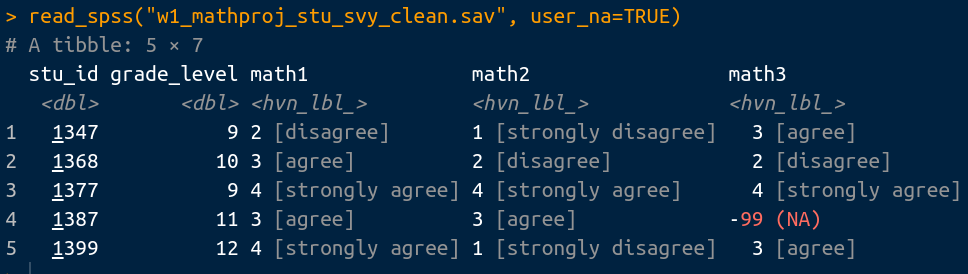

When I load an SPSS file in R, by default it maps all of the missing values to a single NA type (as it did in the examples above). But can also choose to load these missing reason codes by setting user_na = TRUE:

As you can see, I now get a code for the missing value I had in my data earlier. I can also see that the -99 value represents a missing value when I print out the column:

df2 <- read_spss("w1_mathproj_stu_svy_clean.sav", user_na=TRUE)

df2$math3

#> <labelled_spss<double>[5]>: Other people believe I can do well in math.

#> [1] 3 2 4 -99 3

#> Missing values: -99

#>

#> Labels:

#> value label

#> 1 strongly disagree

#> 2 disagree

#> 3 agree

#> 4 strongly agree

I can also create columns with multiple types of missingness:

(x <- labelled_spss(

c(1, 2, 3, -99, 2, -98, -97),

labels = c(

DISAGREE=1,

NEUTRAL=2,

AGREE=3,

OMITTED=-99,

REFUSED=-98,

TECHNICAL_ERROR=-97

), na_range=c(-Inf, 0)))

#> <labelled_spss<double>[7]>

#> [1] 1 2 3 -99 2 -98 -97

#> Missing range: [-Inf, 0]

#>

#> Labels:

#> value label

#> 1 DISAGREE

#> 2 NEUTRAL

#> 3 AGREE

#> -99 OMITTED

#> -98 REFUSED

#> -97 TECHNICAL_ERROR

But all is not sunshine and rainbows. When I calculate the sum() of the values in the previous listing, I’d get a negative number because the missing values aren’t automatically masked out:

sum(x)

#> [1] -286

In general, open software’s support of missing value reasons in tabular data is sparse, to say the least. Missing reasons are typically only specified when loading data in order to convert them all to a single NULL type, so they are lost for data exploration and analysis.

Other than the haven package in R, I wasn’t aware of any other open software implementations of missing reasons until I recently stumbled on the declared R package, which I highly recommend checking out (it fixes the sum() issue I demonstrated above!) I also have been experimenting with my own approach, which I’ve put together in an R package called interlacer. I’m unaware of similar efforts in Pandas / Polars (if you know about any, please let me know!). I have a lot more ideas on this front that I’m excited to share but I’ll talk about them more in a future post…

Similarly, as far as I’m aware, SPSS, SAS, and Stata are the only data + metadata container formats with standard support for multiple, distinguishable types of missingness. Every other data container format I know of (like Parquet) just has a single NA type, and that’s it.

Final Thoughts

Now don’t get me wrong, I know the graphical interfaces and vendor lock-in of proprietary software and data formats will probably continue to dominate for a long while yet. The point I’m trying to make here is that these are not the only issues at play, and I think this represents a potential opportunity.

If we want researchers to use open software and data formats, we need open standards and software integrations that fill the same roles and meet the same needs as the proprietary formats and software currently in use.

Why Don’t You Just Use CSV?

I’m sure this is the first comment on many people’s minds. CSV is the king of open, interoperable formats – just about everything can read and write it. It has unmatched longevity, and I agree that it should be the go-to long-term archival & exchange format if you want something to last and be maximally compatible.

But I think there’s still a place for an open data + metadata container that’s easy to use on a day-to-day basis. To make an analogy, I think that asking researchers to abandon their proprietary formats for CSV is somewhat like asking a regular user of Microsoft Word to switch to pure text files. Yes, it’s great for long-term archival and exchange, but you lose all the formatting. I think we can do better. I think there’s a need for something like the OpenDocument Format for research data. (And then, perhaps, when something like this exists we can advocate for it to be implemented by proprietary statistical software in a similar way Microsoft was persuaded support OpenDocument Format).

What about CSV + a schema with an open standard?

I agree, this would be a great way forward! I think it would be better than embedding metadata in a Parquet or other binary data container for a lot of reasons, particularly for long-term preservation. I’m imagining a simple open format consisting of a CSV and “schema.json” zipped together that would have the three features of SPSS, SAS, and Stata formats I talked about in this post, and more.

There are a number of open standards being developed that could act as the “schema.json” for a format like this. I’m aware of DDI Codebook, CDISC Dataset, BIDS, Psych-DS, and Frictionless, but if you know of other efforts, please let me know!

Unfortunately, none of these open standards are at a point yet for me to recommend to my colleagues to start using right out of the box. The downside of having so many disparate efforts to create standards is that there is no one obvious standard to recommend to my colleagues to use. Many of these standards are missing at least one of the three features I mentioned above, are focused on a niche type of research data, are lacking fully-featured open software editors and libraries, or don’t have converters to and from SPSS, SAS, and Stata formats.

If we want data managers to use our open software and data formats, we need to provide them with an ecosystem that makes their jobs easier.

At the end of the day, here’s the pitch I want to be able to give to researchers and data managers:

When you prepare your data in this open format, and someone asks you for a SPSS file, you can give them one instantly, with the press of a button. No need to export to CSV and manually write SPSS syntax to set variable labels, value labels, and missing value labels; these are all exported from the open format into the SPSS file for you. Similarly, if you start collaborating with someone who uses Stata or SAS, with another press of a button, you can give them a Stata or SAS file with all of the variable labels, value labels and missing value labels properly set in that format.

Furthermore, there’s no need to manually keep codebooks up-to-date for all these exports. Because all the information that usually goes into a codebook is captured in the open format, all it takes is another button press to render a beautiful codebook for your data in PDF, HTML, or whatever format you please.

That said, I’m excited about the direction these open standards are heading, and will write a future post going into more detail about them later!